Avascular necrosis of bone in sickle cell disease describes the death of bone due to vaso-occlusion of vessels supplying a bone that comprises a joint. The death of the bone leads to necrosis that eventually changes the shape of the bone and with this change the joint does not function normally and there is pain initially from the necrosis of the bone and eventually from the destruction of the joint with loss of the joint space.

AVN is a common complication of sickle cell disease, may affect 20% to 50% of people over the age of 35 who have hemoglobin SS. AVN is twice as common in SS with α thalassemia than in SS alone. The incidence is slightly lower in SC disease. It can occur in all types of SCD including Sβ+ thalassemia.

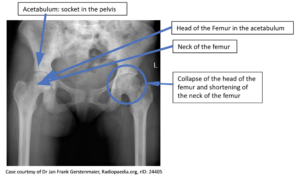

The most common site of avascular necrosis (AVN) is the hip as it only has one vascular supply. Pain from the hip can occur in thighs, back, and knees making the diagnosis a little more difficult. There is eventually limping with symptoms due to the shorting of the leg because of the collapse of the femoral head. The femoral collapse in 73% of cases of individuals with AVN. The pain is increased with weight bearing and increases as the joint becomes misshapen.

The course of AVN is variable, but the progression from MRI detected AVN without symptoms can lead to collapse in as little as four years in some cases. With collapse of the femoral head there can be a leg length discrepancy which leads to increased limping and more weight bearing on the opposite hip which can lead to more pain. Without treatment the hip will eventually fuse to the acetabulum with no pain, but also no movement.

Other joints such as the knees and shoulders can also develop AVN. This may be a joint on one side (unilateral), but is frequently joints on both sides (bilateral). Outside of SCD AVN can occur in other diseases, from trauma, and treatment such as radiation.

AVN can be detected early with a physical examination by an experienced provider, later stages can be seen with an x-ray. The most sensitive imaging is MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging). In people who have AVN in one hip asymptomatic AVN can be seen in the opposite hip with an MRI examination. Generally, AVN is progressive with increased pain and degeneration of the head of the femur and the acetabulum.

AVN can be detected early with a physical examination by an experienced provider, later stages can be seen with an x-ray. The most sensitive imaging is MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging). In people who have AVN in one hip asymptomatic AVN can be seen in the opposite hip with an MRI examination. Generally, AVN is progressive with increased pain and degeneration of the head of the femur and the acetabulum.